Chapter 14 Summary The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning Mayer (2014)

The use of multimedia is important in order to understand the benefits of multimedia learning and how principles are used to support learners. As such, there has been notable research around multimedia principles. In particular, the principles of personalization, voice, image and embodiment have been analyzed as effective ways to base a multimedia resource. Throughout this analysis we will evaluate the previously mentioned principles and their benefits towards learning.

Theoretical Rationale

The theoretical rationale of these principles is used to foster purposeful learning. Therefore, Mayer et al., (2004), elaborates on two approaches; firstly to reduce a learner’s cognitive load and secondly to increase the learner’s motivational commitment. The article acknowledges that there are many external factors that affect the learners cognitive processing. Correspondingly, social cues further support the learning outcomes and are thus essential to support the learners understanding, processing and problem solving of the information. All in all, it is the theoretical approach of social agency that prompts the learner to be engaged as social cues create a learning dialogue that promotes responses. Moreover, this is an enhancement of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning that supports learning.

The goal of these principles is to thus “increase the learner’s feeling of social presence” (Mayer, p.348, 2014), as this increases the learning outcomes and learning process of the individual. Through the use of personalization, voice, image and embodiment cues, we will analyze their effectiveness.

Personalization Cues

The objective of the personalization cue is to make the multimedia resource more conversational. In order to accomplish this Mayer (2014) suggests using first person (I) and second person (you) narratives as well as using personal and direct comments and examples. The personalization cue puts the learner in their shoes through an immersive and role play tone by which the learner is going on that journey.

Voice Cues

The message and intent is impacted by the voice cues. Voice cues support the claim that the audio is human generated and not a monotone robot system. It reiterates the idea that “someone is speaking directly to you” (Mayer, p.351, 2014). Much like robotized voice, a strong foreign accent can also impact the learners cognitive process and understanding of the message. Therefore these factors and use of human voice is critical to support learning through multimedia resources.

Image Cues

The image cue refers to the use of an on-screen character or ‘animated pedagogical agent’ that has the intention of deepening a learners understanding. The animated pedagogical agent may offer explanations and feedback to the learner by speaking directly to the audience and interacting with other elements on the screen such as pointing to essential information.

Embodiment Cues

Animated pedagogical agents experience either low or high levels of embodiment depending on how humanlike they are. On-screen agents with a low level of embodiment are often static, have limited to no facial expressions, and lack eye gaze. Alternatively, an on-screen agent with a high level of embodiment will exhibit human-like gestures and movements, eye gaze, and an array of facial expressions.

Research on the Personalization Principle

When conducting research on this principle, Mayer questioned if students learn more deeply when personalization cues are used. To answer this question an experiment was conducted where students were split up into two groups and shown a short informational video about lightning. Each group was shown a different version of the video, one that contained personalized language cues and one that did not. This experiment concluded that the personalized group of students performed better at a problem-solving transfer test than the non personalized group. This was found to be true for both on screen text and audio information.

In a second experiment, Mayer examined the effects of a personalized and non personalized on-screen agent on student learning while playing a science learning game and came to the same conclusions.

In a third study, Mayer examined the effects of the articles ‘the’ and ‘your’ on student retention in relation to a short narrated animation. The personalized group viewed the video with ‘your’ language and the non personalized group viewed the video with ‘the’ language. Even this small change highly favoured the personalized group. Another study by Wang et al. (2008) showed that students performed better with a polite agent than with a direct agent.

Overall, there is strong evidence that confirms the personalization principle and proves that “people learn more deeply when words are presented in conversational style rather than formal style” (Mayer, p.356, 2014)

Research on the Voice Principle

Mayer (2014) discusses how different accents such as “standard accent to a machine voice or human voice with a foreign accent” (p.357) can result in different performance standards. Participants performed best when listening to a standard accent. In an additional study, Mayer tested students who learned from an online presentation with a pedagogical agent standing next to the slides. Students performed best when the agent used human gestures and voice rather than a machine voice and no gestures. To conclude, Mayer found that students performed best when listening to a non accented human voice rather than a machine or accented voice. Moreover, social cues and gestures helped learners when watching a pedagogical agent.

Research on the Image Principle

Mayer explores the addition of having an image of a speaker on the screen to benefit student learning performance. After 14 experiments varying from static images, a talking head or a cartoon character with either voice or text, the results concluded that “there is not strong support for adding the speaker’s image to the screen” (Mayer, p.360, 2014). The tests conducted were considered low embodiment as the on-screen images did not engage in much “humanlike gesturing, movement, eye contact, or facial expression” (Mayer, p.360, 2014).

Research on the Embodiment Principle

The addition of a high embodiment on-screen image led to higher performance standards of students. Studies have shown that students learn best when the on-screen agents “exhibited humanlike eye gaze, gestures, and pointing” (Mayer, p.361, 2014). Therefore, there is some evidence to suggest that the embodiment principle “people learn better when on-screen agents display humanlike gesturing, movement, eye contact, and facial expressions” (Mayer, p.362, 2014) is true.

Cognitive Theory and Instructional Design Implications

Mayer (2014) explains that social cues that are incorporated by an on-screen agent can have an effect on a learner’s understanding of the multimedia material. For example, “humanlike gestures, facial expressions, eye gaze and movement all serve as a social cue” (Mayer, p. 363, 2014). There is also research indicating that the physical presence of a character on a screen is a social cue that does not affect the motivation of a learner. That being said, Mayer (2014) also describes that on-screen characters can serve as cognitive aids by guiding the learner’s attention through pointing.

Mayer (2014) explains that when creating multimedia instructional messages, the material should be sensitive to social and cognitive considerations. The addressed principles aim to support learning by aligning and following social cues and suggestions made by Mayer, in order to make it real and interactive.

Connection to Teaching

Multimedia learning and principles are key as they provide opportunities to learn using various resources to promote meaningful learning. Notably the principles of personalization, voice, image and embodiment stress the importance of communication and connection. These principles individualize the material, make it realistic and foster interactiveness. As such, using video surfaces and multimedia learning enables the diversity of student learners to prosper in their learning.

References

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369

Mayer, R. E., Fennell, S., Farmer, L., & Campbell, J. (2004). A personalization effect in multimedia learning: Students learn better when words are in conversational style rather than formal style. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 389–395.

Wang, N., Johnson, W.L., Mayer, R.E., Rizzo, P., Shaw, E., & Collins, H. (2008). The politeness effect: Pedagogical agents and learning outcomes. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies , 66 , 98–112

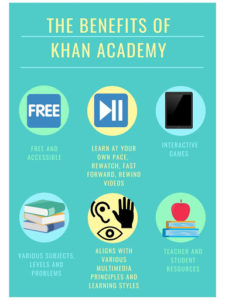

Seesaw was the app that I reviewed and one of the downsides that I came across was that they charge $7.50 per student. Although I am sure that there are funding options that you can seek out, Khan Academy Kids is free, which makes it that much easier to see how it works for your class.

Seesaw was the app that I reviewed and one of the downsides that I came across was that they charge $7.50 per student. Although I am sure that there are funding options that you can seek out, Khan Academy Kids is free, which makes it that much easier to see how it works for your class. TedEd Talk is also an interesting app that I can see beneficial to use in an elementary classroom. They have a wide variety of subjects, which could be useful, especially if students are doing something inquiry based.

TedEd Talk is also an interesting app that I can see beneficial to use in an elementary classroom. They have a wide variety of subjects, which could be useful, especially if students are doing something inquiry based. While reviewing this app, I evaluated it using the

While reviewing this app, I evaluated it using the  My overall experience while using this app was positive. It seemed to be user-friendly and I liked being able to look at other activities posted by teachers to get inspired. I also think an app like this would work well for remote learning, as students can review the materials posted by the teachers and submit their work within the app. Another feature that caught my attention was that the app allows you to import work directly from Google Drive. If you are trying to create a portfolio and want to include something from another document outside the program this seems like a useful tool. Other benefits that I came across are that it can be used for a variety of ages, multiple subjects and student collaboration.

My overall experience while using this app was positive. It seemed to be user-friendly and I liked being able to look at other activities posted by teachers to get inspired. I also think an app like this would work well for remote learning, as students can review the materials posted by the teachers and submit their work within the app. Another feature that caught my attention was that the app allows you to import work directly from Google Drive. If you are trying to create a portfolio and want to include something from another document outside the program this seems like a useful tool. Other benefits that I came across are that it can be used for a variety of ages, multiple subjects and student collaboration.

Recent Comments